A Tribute to Merv Wortley Senior

Recently, it was with great sadness that we received news from Jenny Rigg of Ruby Plains Station, Halls Creek, WA that Merv Wortley Senior had died.

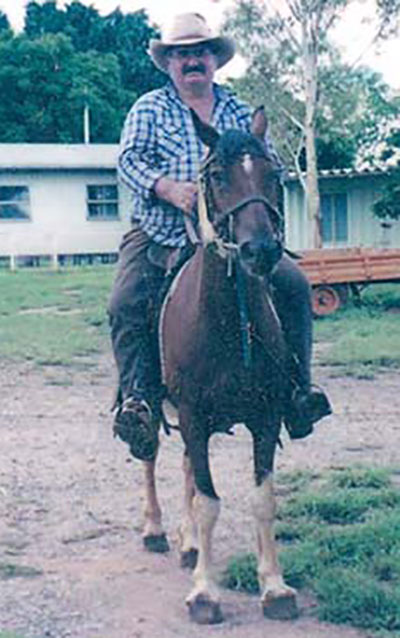

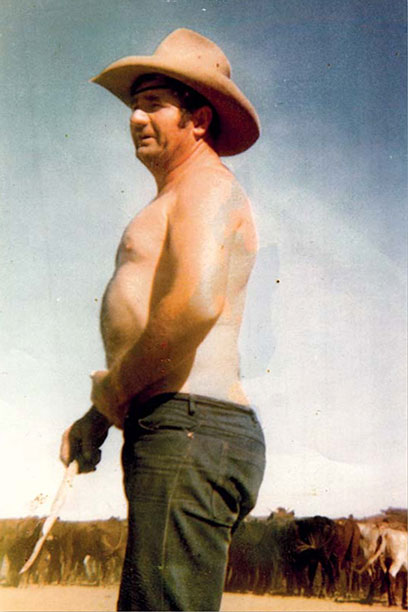

The father of Merv Wortley, current manager of Ruby Plains, Merv Senior was almost 80 years of age and had spent most of his life in the bush working with stock.

Cattle and sheep properties around the Channel country and North of Australia were his home and he had many a yarn to tell.

Lyle and Helen were privileged to meet with Merv each year at Ruby Plains while on their annual business trips and Merv was willing to sit with them and allow them to record some of his accounts and yarns.

In tribute to Merv, we are sharing the article about him, from Helen Kent’s coffee table book, “Stories of Australian Country People“, below for all to read. Merv was a gifted story teller and the article recounts some of his personal story and other yarns. Each year at Ruby Plains, Merv would usually say “Come next year and I’ll tell you another story.”

That opportunity has now gone this year and Lyle and Helen will miss the old stockman.

Our sincere sympathy and condolences go to Merv, Jenny and Merv Senior’s family, to all at Ruby Plains, and the many people and friends who knew and appreciated Merv Wortley Senior.

An Outback Life

Merv Wortley Senior

Ruby Plains Station, Halls Creek, Western Australia

(Lyle and Helen interviewed Merv during 2007)

Merv’s dad was killed on the Kakoda trail during the WWII and as Merv tells the stories of his childhood and records the days of his youth, it’s not at all difficult to picture a tough and wiley little boy.

That boy would often be seen on the roads around Windorah in south-west Queensland trotting along in a horse drawn sulky. He was out there, noticing where sheep had perished in paddocks near the road. He was out there for a purpose and he was sometimes aware that property owners would be watching him “…with binoculars, through their windows. So if I’d see a dead sheep, I’d get down off the sulky, pull off a branch from a tree or bush and make out I was giving my dog a hiding! That poor little dog, wondering what was going on, but then I’d chuck that branch on the roadside near the dead sheep and get back on the sulky, and go along. When it was dark, I’d go back, find that branch, get through the fence and collect the ‘dead wool.’ It was worth a pound for a pound and it may have been the wrong thing to do, but why let it rot away into the ground when somebody could make a few bob out of it, eh?”

In the early 1950’s, at the age of 14, Merv ran away from home and spent four years working at Keeroongooloo Station, south of Windorah. Merv pronounces it, “Kurungla” -like no one else can.

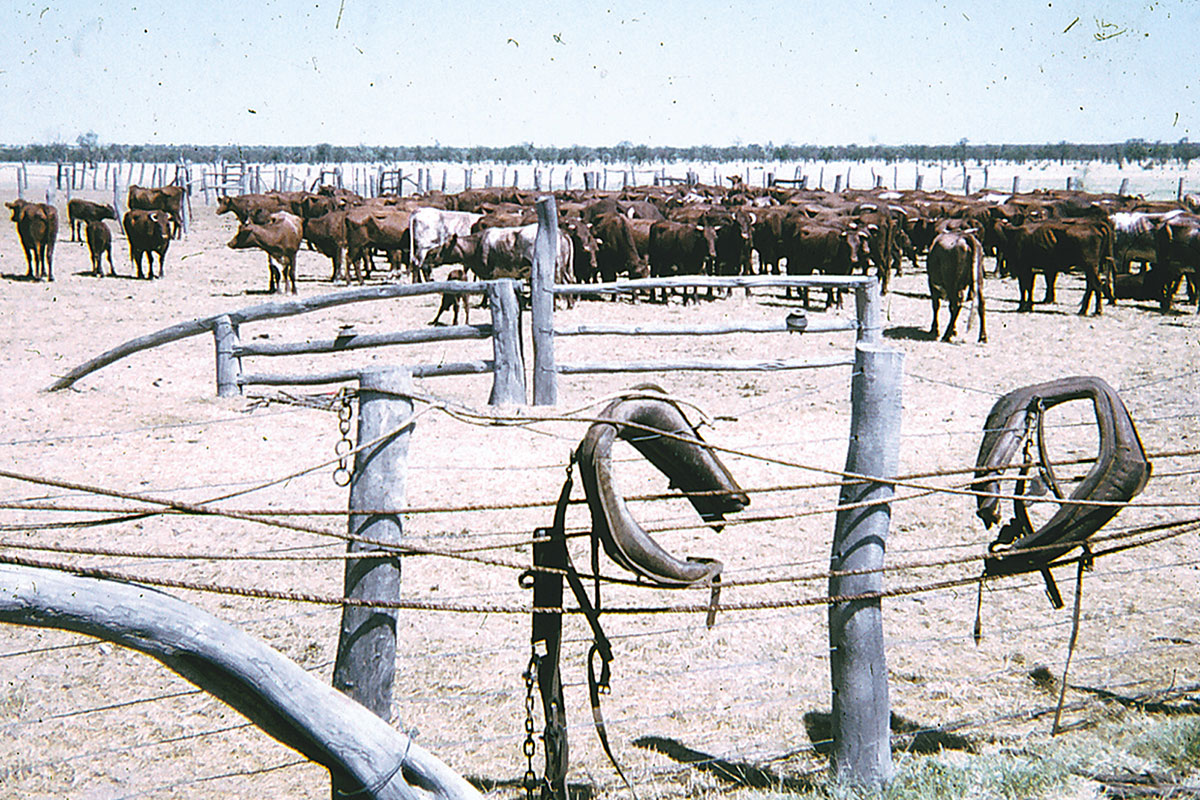

Merv has been around horses and cattle all his life and his youth encompassed a time when bronco-branding was the method used to brand calves.

Merv records this ‘account’ of when he was a headstrong youngster at Keeroongooloo. In an incident that the young Merv would be unlikely to forget, he describes the bronco-branding method with great accuracy.

The head stockman had put Merv on a bronco horse to rope the calves for branding. Merv wasn’t paying much attention and his catching rope kept missing the calves. The head stockman warned, “Make sure you catch the next calf.” Merv missed the calf and the next thing he was dragged from his horse and the bronco rope attached to another horse was tight around him. He hit the ground and was pulled up to the bronco panel. The other men put leg ropes on him, bronco style, and scruffed him to the ground like they would a strong calf. As the castrating knife appeared, the cheeky kid was “singing out for mercy!” Thankfully mercy was shown and he adds, “I never went through that deal again. I made sure I caught the next calf! I thought, ‘I’d better do what I’m told!’

The head stockman had the last word, one that Merv would never forget: “That wasn’t very hard was it?”

Apart from that scary incident, Merv remembers the days of traditional bronco- branding with satisfaction. He recalls memories of a big black horse named ‘Pig’ and other strong bronco horses which, along with a skilled catcher, made the work easy.

Following a suggestion from the manager at Keeroongooloo to “see how other places do it,” Merv joined a droving team and spent several years transferring cattle from Charleville in Queensland, to Moree in New South Wales. Each drove took 16 weeks, followed by a journey of 16 days to bring the horses back. As he waited for the next mob, he worked on Boatman Station, out of Charleville. Merv married Lois Johnstone in 1965 and they returned to Keeroongooloo where he ran the stockcamp for 25 years.

The stockcamps often had between 20 to 30 men and around 500 working horses and the ways in which young men were recruited were questionable to say the least. Merv, one time, was at Eromonga waiting to catch the mail truck out to Keeroongooloo, when his swag and saddle were taken and then hidden. It was an effort on ‘someone’s’ part to keep him at a nearby station, where 160,000 sheep needed shearing!

He flatly refused to stay and stubbornly let them know, “Well, I don’t care, I’m not stopping here to work sheep!” He travelled on to Keeroongooloo without his swag and saddle, which were sent on to him the following week.

Alternatively and strategically, young workers were shouted too many drinks at a local pub, and they’d wake up the next morning on a drove or at another work place. “That used to go on a lot,” said Merv.

During the telling of these life stories, Merv pauses, then asks “In all your travels, have you ever seen that Min Min Light?” As we answer with a ‘No,’ he responds, quickly. “I’ve seen a mob of ‘em!”

Merv first encountered the mysterious light as a kid, when he and his younger sister were out setting rabbit traps. They could see the lights of the station and when they saw a bobbing light coming towards them, decided it must be the station-owner carrying a lantern. Putting out their own light, they sat quietly with their dog in the long grass. Watching through the grass, they saw the light begin to circle around them, at a distance. Then it went out and re-appeared behind them and then, somewhere else. Merv adds, “That’s when the hair stands up! It’s like ‘he’ (the light) is studying you, looking at you! Another strange thing, that little dog took no notice of the light and I’ve never known horses or dogs that took any notice either.”

He tells of ‘roo shooters, armed with quick-action shot guns and high-powered scopes, who on horseback, fearlessly charged the light, firing well-aimed shots.“ ‘He’ would look at them,” as Merv puts it, and then vanish and appear in another place.

A close relative (younger and very similar!) first saw the Min Min light while bringing in horses in the dark, very early one morning. Forgetting all else, this young ringer galloped all the horses, some hobbled, straight back to the station, where he received a kick in the backside from the manager and a verbal reprimand. “That won’t hurt you!” he was told.

Was that the kick or the light, or both?

A motorbike breakdown at nightfall, a long distance from the station, saw this same relative resigned to spending the night camped near the bike, knowing someone would come to get him in the morning.

“But,” and Merv takes up the yarn, “here came the light along the top of the sandhill where he was and as it came towards him he said to himself, ‘Well, I’m a goner’ and he just put his arms and legs around that motorbike an’ hung on! He was promising that Min Min light, “Well, if you’re gunna take me, you’re gunna take the bike too!”

The light went around a couple of times, went down onto the flat and disappeared. And the bike rider lived to tell the tale.

Merv has endured rat plagues in the Channels and he’s caught brumbies for the Indian army. Among hundreds of different experiences, he’s lived alongside immigrants who, following the completion of the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Project, came to Keeroongooloo and constructed 100 miles of netting fence. In the 1950’s, driving from Quilpie to Windorah on the mail truck at night, it was common to see camp fires about 10 miles apart, knowing that each lot of campfires represented a mob of at least 1,000 cattle. Merv came to Ruby Plains in 1988 and has been there ever since. He reckons it was good working at Ruby as head stockman and in 2007 as bore runner and he hopes to retire there at the station and watch his grandchildren grow up.

Thanks Merv, we appreciate you.

Merv’s Yarns

In 2014, Merv Wortley Senior, from Ruby Pains Station near Halls Creek in Western Australia, was willing to share some more vivid memories … revealing, interesting, sometimes humorous, sometimes sobering.

The following yarns, embedded in Merv’s memory, come from the 1950’s, when he was employed at Keeroongooloo, in far west Queensland. For Merv, storytelling is as natural as breathing.

Introducing the story is the most awkward stage.

“Now, where do I start?” he ventures. “The only way I can tell it is the way I practically seen it.”

There’s a brief pause and he begins.

… Other Places sure did things different

“An’ when I was at Keeroongooloo, that ol’ fella, that Klacy House, the manager, he told me, “You should go and see how other stations do it. Go down … go here … go there …” So Merv went. “Before I left,” he tells, “that Klacy House, he said, ‘If you go broke anywhere, go to the police station. I’ll send you money’ ”

Merv embarked on a journey of discovery.

“ … an’ I found out; those other places sure did things different!”

Merv Head Stockman at Keeroongooloo

Merv travelled to Womblebank Station, outside Mitchell, where Johnny House, the son of Klacy, was the manager. At Womblebank, the stockcamp there were mainly indigenous workers and according to Merv, the head stockman was ‘half Chinese.’ An’ one day, Merv adds “after we got a big mob rounded up he told me I wasn’t working hard enough” Merv figured that the others had been complaining about him. “Well, so I got right in there an’ I threw half-a-dozen mickeys (bulls)” Merv coughs and continues, “An’ you know? That head stockman, he comes to me an’ he says, ‘them fellas, they’re pulling out! They reckon you’re taking work from them!’ ” Merv, healthy, fit, strong and stirred up, dealt with the situation the only way he knew how.

“I took one of those fellas with me an’ we had a fight. I had ‘im on the ground. I beat him! Then there was this second fella … an’ it was a dirty fight! I beat him too!” Merv pauses, and chuckles, “I never had two better mates after that! I stayed on there at Womblebank for a year or so.”

All for love

“Then,” he reports matter-of-factly, “I was goin’ with a girl from Mitchell. It was 90 miles out to Womblebank from Mitchell an’ I had me own horses at the town. At the time I bought a blue horse from a fella by the name of Tony Pacey.”

At the end of a week’s work at Womblebank, Merv had definite plans. “It was Friday afternoon on dark an’ I was goin’ to town to see that girl.”

There’s no doubt the young ringer was keen. “An’ that horse, never shod him once, an’ there’s a grid at the station an’ he’s flying over it, no trouble at all.”

Time and distance was no deterrent, 90 miles there and 90 miles back.

“I’d arrive at daylight next morning an’ on Sunday afternoon, I’d get back on ‘im again. Get back to work on Monday on daylight, with matchsticks in me eyes!”

Hupperdy

“That ol’ aboriginal fella was telling me, ol’ Hupperdy was his name, only had one name, Hupperdy. Don’t know how you’d spell it. And he was there at the station all his life. And in the previous years, when the people who were on the station went out to work, the aborigines come in and killed most of the white women an’ the kids an’ that. When the station blokes come back from work an’ seen what went on, well the owner, he just grabbed his men an’ followed ‘em out to a plain way out the back an’ that’s where he got stuck into ‘em; you know, with a gun, and wiped them all out. And this Hupperdy, he was only a boy; he climbed up in a tree but the tree was only just as high as a man sitting on a horse and uh, they just grabbed ‘im off the tree and chucked him on the back of a horse and took ‘im home and tied that ol’ fella up on a dog chain and chucked a bag down there for ‘im … and he just lived like that until he come good and learned to talk English an’ he sort of grew up there for evermore.”

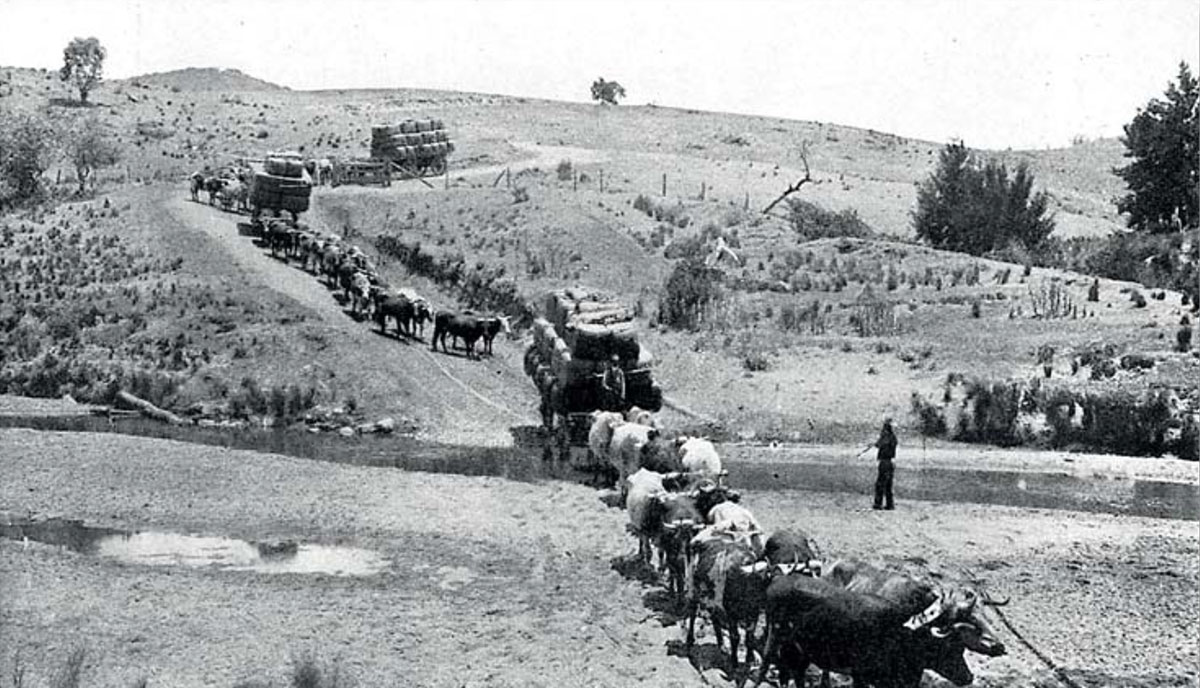

The Bullock Team

“Yeah, well Hupperdy told me and also the previous manager an’ I seen it writ down in the big book there too at the time. But, well, where do we start off?” Another brief pause follows. “Well, this is Keeroongooloo, say here,” Merv explains, indicating with a forefinger and tapping a spot on the table top. “Well, 25 miles straight down here to Pulpirie that’s the big waterhole and down at Pulpirie are old ruins there of a house. That was where the bullock team mob come up; I think they were on the road four to five days; four days at least. This bullock team was all loaded up with wool and I don’t know where they was taking it to, but the driver he pulled up there and went inside there … talking to that woman there, or whoever gave ‘im a drink of tea… probably a ladies’ man I ‘spose he was, those days. And well, he went inside and he had a good drink of tea there. Well, a strong wind was comin’ off the waterhole. Them big ol’ shorthorn bullocks that they used in the teams … they hadn’t had a drink for four to five days and they were perishin’.

An’ those ol’ bullocks they smelt the water like that and they went straight down there an’ straight over the big high bank and down to the water level there; straight over that bank an’ the wagon come straight down over them an’ they were never seen again. That driver, he come out and looked around, looked like that an’ as he looked, well the tail end of the big ol’ bullock wagon was just going over that bank like that an’ when he got over to there … not a thing! A big deep hole yeah; very deep, never been dry. Never been dry.

The account ended abruptly; other thoughts and memories vying for attention.

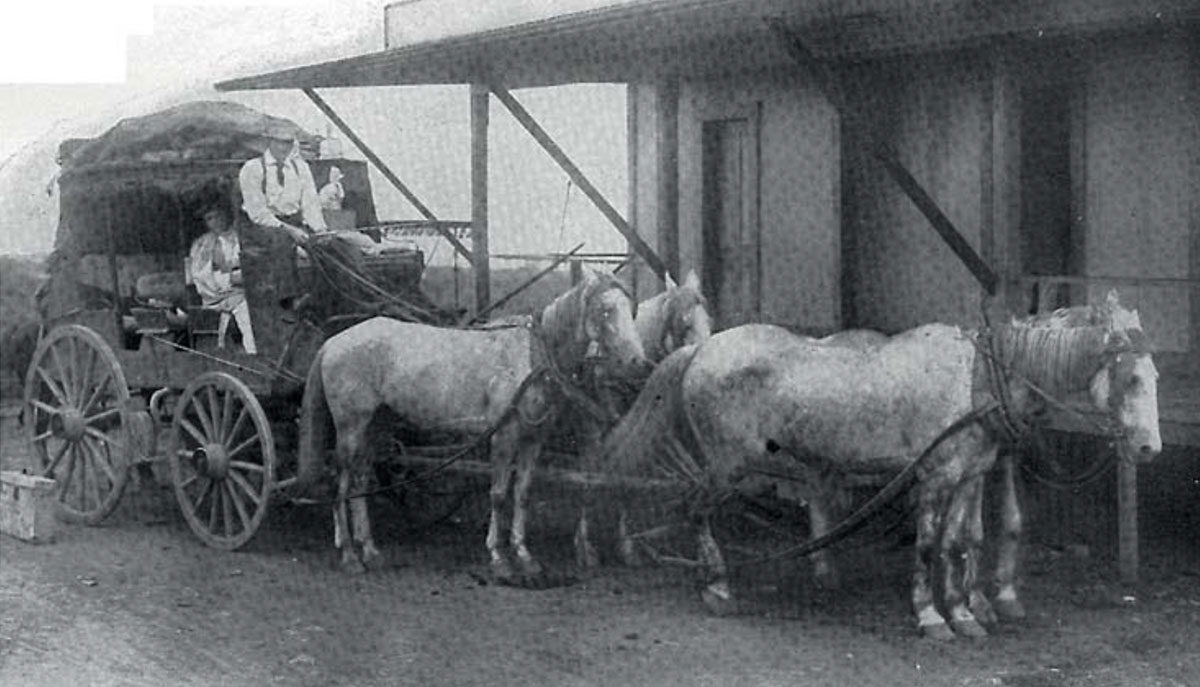

The Stagecoach

“Yeah, well then,” Merv continues. “There’s that and then you go straight down the stock route. (Merv pronounces it ‘rowte’) It’s goin’ down towards Mount Howitt Station. You been to Mount Howitt?” he queries.

“Well, you see, then the road goes straight down the netting fence an’ well, then you come to this first place; It’s the spell paddock and that’s the house where the boundary rider used to live.”

Merv’s work-worn forefinger is an effective marker as he traces the directions on the tabletop.

“And you go past there an’ you come to this Marama Holdings. The State Government used to own all along that country many years ago, from way back. And they got a Chinaman cook there to change the horses on the stagecoach for the Cobb & Co that come across from Eromanga. Well, the stagecoach was comin’ down this big hill an’ the horses musta’ been galloping a bit too fast an’ the coach rolled and killed the passengers and the driver.

So, here’s that Chinaman cook an’ he knew the stage was comin’. Well then, he’s busy there waitin’ an’ getting things ready, an’ next minute, he heard the noise of the stagecoach coming. He heard the whip crackin’ an’ a bloke singin’ out. He heard the wheels rattlin’, you know how they’re rattlin’ as they’re comin’ in?” Merv asks.

“An’ he ran out to see how many passengers there were so he could get the food ready. No one there!” Merv’s searching eyes re-enact the moment. “He looked, like that, again. No one there!

“Well he just packed up an’ he went! Never seen him no more.” “And that’s what happened”

That stagecoach would’ve been coming across from Mount Howitt” Merv explains. “You can still see the stagecoach road comin’ across from Eromanga.”

“It seems funny, but … and Merv hesitates “I don’t believe in ghosts meself, but still it’s a hard thing to get outta’ ya’ head when something like that happens an’ ya see it write down in different books an’ managers tell you and that ol’ Hupperdy, he was telling me … he was there when it all happened.

“Well then,” Merv continues “ … as the years went on an’ I was there at Keeroongooloo an’ there were these two ol’ drover blokes. Well, they heard exactly the same thing” and Merv backtracks.

“So, I was there at Keeroongooloo an’ I looked out an’ I just can see someone ridin’ up an’ I thought, “Gee whiz, it’s nobody from the camp, with no shirt on … unless they had a big fight down there. And when I ran down, here’s this old bloke in his long johns … no skin on his backside. And he said, ‘where’s the manager?’ an’ I said, ‘I dunno. I dunno if he’s up yet. I’ll go an’ get ‘im’ an’ he said, ‘tell ‘im to bring some clothes down for me too.’

“Poor ol’ fella, an’ we got talkin’ away there for a little while an’ away I went up there then an’ the manager he come down. Klacy House was the manager, only a short man, but a very happy sorta fella … red face ol’ bloke he was, an’ he went down to this fella an I heard ‘em talkin’ an’ that ol’ bloke was sayin’ that he’s not gunna go back down to that house. He was tellin’ the manager what he heard. He said the same thing. He and his mate musta been in their swags an’ they heard the coach comin’, heard the rattlin’ an’ the driver singin’ out at the horses an’ the whip crack. When they went outside, well, there was no one there! So, that’s when they grabbed a horse each and shot through. That ol’ bloke, he just mounted his horse bareback, in his long johns.

“The manager he said, ‘where’s your mate?’ an’ the ol’ bloke he said ‘I dunno where he is, but he took off one way and I took off the other way.’

And while we were talking of this occasion, word came through to Klancy House on the pedal wireless. There’s a call saying that this other ol’ bloke from down at the house, he lobbed in at Eromanga town, in his long johns! The policeman from Eromanga said ‘bring some clothes in for this man, he’s only in his long johns.’ ”

Merv’s chuckle is contagious.

He adds, “Well, around the road going to there, Eromanga is 65 miles. I dunno what it is through the hills, but it’d be heavy goin’. It’s the most roughest country I’ve ever seen through there. I used to run a lot of cattle in through there, but oh, I dunno how that ol’ fella found his way. All I can say is that he was a very good bushman.”

“Well,” Merv states emphatically, “that’s what I heard that ol’ bloke sayin’ to the manager. ‘I ain’t going back,’ he said ‘ I ain’t goin’ back! If I gotta go back there, you might as well shoot me!’

“Yeah, so,” Merv concludes, “ … they must’ve got a terrible fright.”

A shameful story

This is the story, as told by Merv Wortley, of a shameful incident in a place and time in Australia’s relatively recent history. A young man at the time, Merv was pulled as if by a black and emotionally charged magnet, to witness the following event.

“It was around Charleville,” Merv speaks quietly. “I was drovin’ with a bloke called Charlie Williams … horse tailin’ with ‘im … for a good while … a long time.”

Merv’s memory is specific.

“Two packs and a swag I had and he’d fill me packs with food; a carton of beer … a bottle of rum.” The arrangement suited Merv.

“So, away I went … to Moree, delivering some horses for that Charlie Williams”

“So, I was ridin’ along and I see this drover bloke, pulled up on the side of the road. He had all blokes with ‘im and about 60 horses and I went a bit closer to have a look.” Merv hesitates; collects his thoughts.

“And this gypsy van is pulled up there too eh? … a covered-in van and two horses pullin’ it. Heavy horses they was. And this drover bloke; he pulls out some money … I dunno how much … an’ he gives it to this gypsy fella and there’s this gypsy fella’s wife, cryin’; an’ a girl… about twelve-year-old … their daughter, I’m thinkin’. The gypsy fella… he says ‘Thank you’ an’ that drover grabs that girl by the arm an’ pulls her onto his horse and off he rides. And that mother is cryin’ and the father give her a whippin’.”

The old stockman falls silent. Then, “That was a wicked thing to do wasn’t it?” he mumbles.

“I told my mother about that.” -She said it used to happen a lot, those days.”

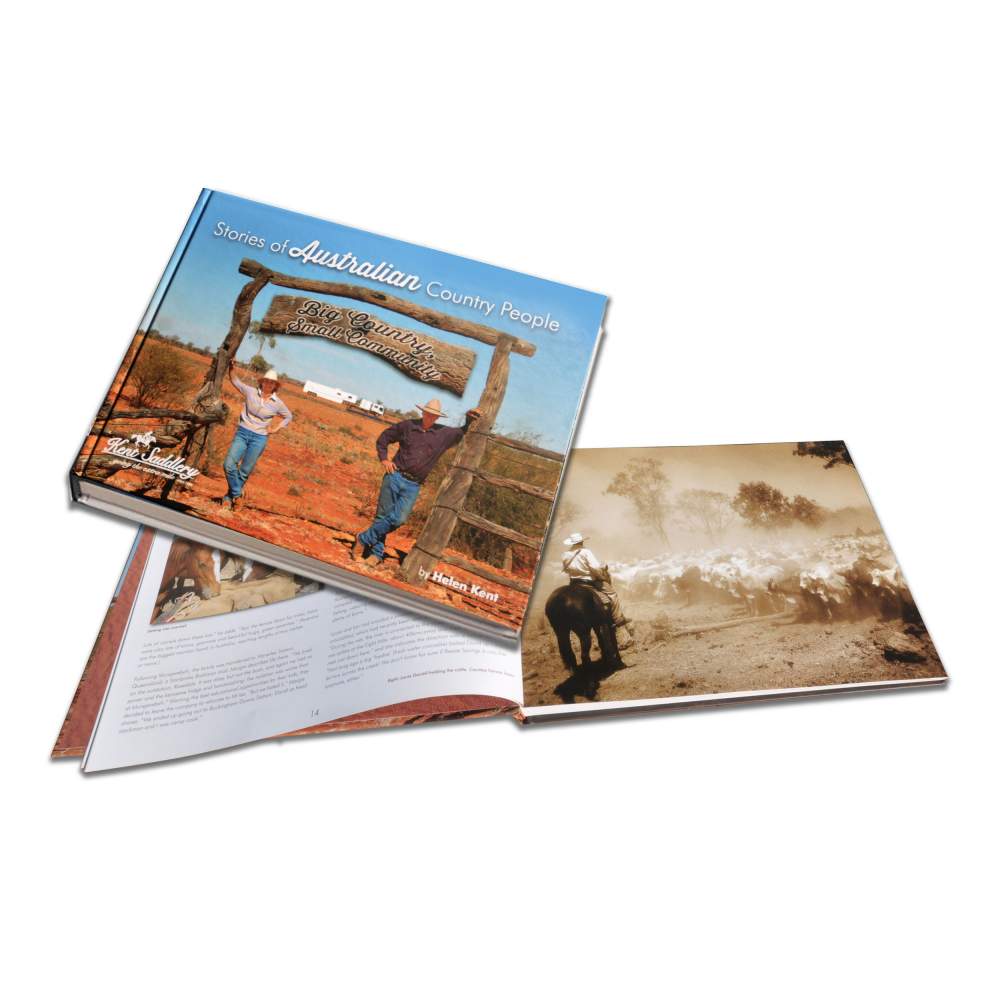

Over 35 stories…

For more great stories like this one of Merv be sure to check out Helen Kent’s coffee table book, “Stories of Australian Country People”.

This beautiful book showcases stories and photos of country people from throughout the Kimberley, Pilbara, Queensland and the Northern Territory.

A great gift for a loved one…

Or treat yourself by adding some memorable Australian country stories and photos to your book collection!